At Stripe, we’re working to empower entrepreneurs across the globe by making the process of starting and scaling an online business simpler. In the ongoing pursuit of improvements to our products, services, and the economic infrastructure of the internet, we try to keep the greater meaning of what we’re doing in sight at all times. We often ask ourselves: “What future are we creating?”

We think about this question in a few ways:

Technological advancement: Are we providing tools that enable businesses to thrive?

Human betterment: Are we fostering equal opportunities?

Global forethought: Are we doing our part to improve the state of the world around issues such as climate change and economic disparity?

The latter—global forethought—has moved increasingly into focus for us in the past year. For climate change in particular, it’s clear that the world is at a crucial tipping point. Anthropogenic emissions of carbon are accelerating, and our collective behavior today will no doubt determine the world we live in 30 years from now. Patrick Collison, Stripe’s CEO and cofounder, asked me to come up with a proposal for what Stripe should do. More precisely, he asked me what, exactly, it would take for Stripe to become a carbon-neutral company.

I quickly learned that you don’t need a full team to take this on. Though I was entirely new to carbon neutrality, this was a surprisingly reasonable undertaking for a company of our size—we became carbon neutral in a matter of months. Here, I’m sharing an overview of what I learned about the carbon offsets industry, what climate mitigation options Stripe considered, and the decision-making framework we used. There’s also a step-by-step worksheet aimed at helping you develop your own sustainability program, no matter the size of your organization.

We think it’s important to share these journeys, and we’d love to hear about yours.

—Ella Grimshaw

Background

Why does climate change matter?

Last year, the World Economic Forum named climate change as the biggest global risk facing business and the economy. Climate change is ranked as one of the top trends that will shape global developments over the next 10 years, for better or for worse. Furthermore, while both the public and private sectors have stepped up in efforts such as the Paris Agreement and energy efficiency targets, we will need to do more.

Specifically, to limit the most dangerous impacts of climate change, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) estimates that the global community cannot exceed emissions above one trillion metric tonnes of carbon—that’s 1,000 petagrams of carbon, or PgC—in order to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial levels. The 2 degrees Celsius target was deemed as the manageable threshold for climate change by the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; it’s long been seen as the largest average global temperature increase that will mostly keep climate risks within historically observed boundaries. Although any warming is expected to increase risks—such as sea level rise, forest fires, changes to precipitation, and extreme weather—many view 2 degrees Celsius as a danger threshold beyond which the risk of irreversible harm is unacceptable, and could become disastrous.

Alarmingly, the world had collectively emitted 515 PgC (52 percent of the allotted 1,000 PgC) by 2011—and we may exceed 1,000 PgC by 2045.

How is climate change being addressed today?

Today, common approaches to mitigating climate change include (a) energy emissions and efficiency standards, such as renewable energy requirements for utilities or efficiency requirements for cars; (b) market-based and carbon pricing approaches, such as a carbon cap-and-trade system; and (c) government-supported research and development. Some businesses are legally obligated to buy emission permits (known as the mandatory carbon market); unregulated businesses can voluntarily offset their own emissions (this is the voluntary carbon market).

In the mandatory carbon market contexts, state (e.g., the California Air Resources Board Cap-and-Trade Program), regional (e.g., the Western Climate Initiative and the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative), or national (e.g., China’s carbon emissions trading program) programs regulate the amount of greenhouse gas that can be emitted. This is often done via a cap-and-trade system: The government sets a total emissions cap and distributes emission allowances to businesses, often through auctions. The cap is reduced over time, slowly forcing companies to be more carbon efficient. Companies must buy permits on the market to emit carbon, so they look for opportunities to reduce carbon emissions. In regions where carbon caps are the law, power-generating companies (i.e., power plants) are generally regulated, and are therefore required to participate in the mandatory market.

In the voluntary market, there is no cap-and-trade component. Instead, many organizations set their own carbon reduction targets and purchase carbon offsets to compensate for the operational emissions they aren’t able, or choose not to, to avoid themselves.

How do we know if these efforts are making a difference?

Both the mandatory and voluntary markets are measured by their ability to eliminate large quantities of greenhouse gas from the atmosphere.

The Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), a cooperative initiative of the Northeastern and Mid-Atlantic United States, recently announced that it will reduce the market cap another 30 percent between 2020 and 2030; California’s carbon market has been steadily reducing the market cap since 2013. Lower caps mean there are fewer allowances to go around, which tends to make emissions more expensive (though it’s not necessarily or always a direct link). This pushes regulated businesses to reduce their carbon emissions, often by using less energy or using lower-carbon sources of energy.

The mandatory carbon markets—including the European Union’s Emissions Trading System, the RGGI system on the East Coast, California’s Cap-and-Trade Program, and a large but nascent system in China—have had mixed success. The principal failures have come from market fluctuations from too many allocations. But efforts to address that are underway: Many of the larger markets, including those in the U.S. and the EU, have reduced allocations with the goal of driving up prices and creating pressure to drive down carbon emissions. The Chinese system is too new to evaluate.

In the voluntary market, the volume of carbon offsets sold provides some sense of how well the market is doing. According to the annual State of Voluntary Carbon Markets report from Forest Trends’ Ecosystem Marketplace, since 2005, over one billion metric tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) have been sold, with 63.4 million metric tonnes sold in 2016 alone—which the Environmental Protection Agency’s Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator equates to taking over 13.5 million passenger vehicles off the road for a year. Furthermore, many Fortune 500 companies announced new or more ambitious carbon reduction targets following the adoption of the Paris Agreement, which was agreed upon in 2015 and went into effect in 2016. As outlined by the World Wildlife Foundation in an April 2017 report:

“Sixty-three percent of Fortune 100 companies have set one or more clean energy targets. Nearly half of Fortune 500 companies—48 percent—have at least one climate or clean energy target, up 5 percent from an earlier 2014 report. Accompanying this growth is rising ambition, with significant numbers of companies setting 100 percent renewable energy goals and science-based [greenhouse gas] reduction targets that align with the global goal of limiting global temperature rise to below 2 degrees Celsius.”

Despite this, the voluntary market experiences its own volatility. The Forest Trends report notes that carbon offset sales shrank by 24 percent between 2015 and 2016, with millions of tonnes of CO2e offsets reported as unsold. These fluctuations in demand can cause concern among project developers, who need steady pools of investment to continue development.

What does it mean to be carbon neutral?

Being carbon neutral means having a net zero greenhouse gas emissions footprint. An organization’s emissions footprint includes emissions from all of the company’s activities, including office and buildings’ energy use, manufacturing and industrial processes, corporate travel, and other factors. With current technologies, the majority of organizations will produce some sort of emissions. Many organizations focus first on reducing their emissions, often by investing in energy efficiency (perhaps by turning off all lights overnight, or only running their heating system during certain months), and then offsetting those emissions that are too costly to mitigate directly using other methods. We’ll explain a few of those methods later on.

The term “carbon neutrality” encompasses all climate change pollution, not just carbon dioxide emissions. Other important greenhouse gases include methane, nitrous oxides, and some refrigerants. Globally, carbon dioxide is by far the largest contributor to climate change, followed by methane.

What motivates organizations to voluntarily become carbon neutral?

Many companies already invest in robust sustainability and carbon offsetting programs. These programs are driven by numerous factors, many of them ultimately boiling down to the importance of companies taking social and environmental responsibility. “Many of our stakeholders […] are interested in sustainability and taking action towards it. We hold ourselves accountable to them and believe that businesses have a responsibility to elevate the conversation around global climate change,” said Chelsea Mozen, Senior Manager for Sustainability and Energy at Etsy, which is on its own carbon-neutral journey (Etsy is aiming to power its operations with 100 percent renewable electricity by 2020). Elizabeth Willmott, Environmental Sustainability Program Manager at Microsoft, noted that “cloud-powered transformations can help address climate change and enable countries, companies, and cities to grow and operate sustainably.” Max Scher, Sustainability Manager at Salesforce, pointed out that climate change amplifies global inequality and that “companies have a key role to play in driving towards equality for all.” And Anna Escuer, Carbon Accounting and Offsets Program Manager at Google—which has been carbon neutral for a decade—highlighted how “the science of climate change shows that greenhouse gas emissions have tangible adverse effects that pose long-term threats to our planet, our population, and our businesses.”

We were—and are—inspired and motivated by what these and other companies have been able to do, and decided that Stripe should have a similar program. Not only did we feel it was the right thing to do—we all play a part in anthropogenic climate change—but unregulated businesses need to help close the gap between the emission reductions promised by governments and what scientists predict is necessary to stabilize climate change.

Stripe’s journey to carbon neutrality

“What would it take to make Stripe carbon neutral?”

When our CEO, Patrick, first asked, we didn’t have an answer for this. But we did know:

There was ample opportunity to reduce our impact. Though Stripe doesn’t make a physical product—our API powers online commerce for hundreds of thousands of businesses around the world—our operations still contribute to a global problem. We focused on measuring our general use of gas and electricity, the cooling of our facilities, and the energy consumed by our servers and travel.

We wanted our solution to be quick to implement, high impact, and cost-effective.

Our journey to carbon neutrality took place in three phases:

Scoping: Identifying what mitigation options were available in the world;

Deciding: Choosing which option made the most sense for Stripe;

Executing: Making it happen.

Phase 1: Scoping

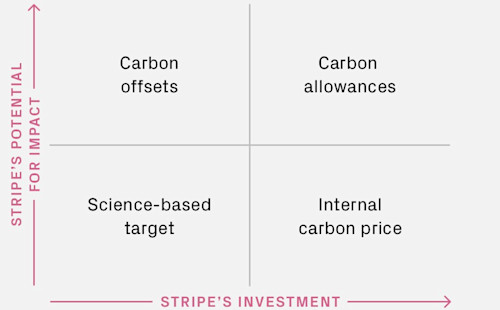

First, we needed to understand what mitigation options were available to us—we wanted to do something that was truly substantive, not something that just sounded good. We assessed each option on the axes of impact and investment.

We defined these terms for Stripe as:

Stripe’s potential for impact

Time: How quickly can Stripe implement the solution?

Influence: How much will this help move the needle on climate change?

Amplification: Can Stripe encourage other companies to also invest in sustainability?

Stripe’s investment

Cost: How much of Stripe’s operating capital will we spend on developing this program?

Operational requirements: Can this work be tackled by Stripe’s internal team of one, while leveraging external partners?

This framework allowed us to prioritize the options we found by the highest impact and a manageable (or low) investment. An inherent tension exists between these two variables—when you optimize for cost (low investment), you’ll often find lower-quality options (low impact). Stripe paid close attention to this tradeoff throughout our research in order to find a balance that felt right based on our emissions profile (we’ll talk more about this a little later). Any company that undertakes this process will have its own assessment of impact and investment, as well as how to balance the two.

The four approaches we considered were: carbon offsets, carbon allowances, carbon pricing, and science-based targets.

It’s worth noting that science-based targets are not a carbon-neutral emission reduction strategy—they’re more a framework for how to set emission reduction targets. However, for Stripe’s purposes, we included them as part of our evaluation, alongside more directly strategic approaches.

1) Carbon offsets

Since Stripe is under no legal obligation to offset our emissions, we would participate in the voluntary carbon offset market. Most offset projects available today can be categorized into one of the following project types:

Renewables

Forest and land use

Methane

Efficiency and fuel switching

Household devices

These projects are managed by offset providers. We researched a few, including 3Degrees, Bluesource, NativeEnergy, Natural Capital Partners, and TerraPass.

Each provider and project focuses on a different selling point. They vary in price and location, and some even claim co-benefits such as habitat protection or job creation. Given the array of options, companies are able to choose what makes sense for them.

| Project type | Volume transacted 2016 | Averge price ($/tonne) | Spread between min & max price ($/tonne) | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| REDD+ | 9.7 MtCO2e | $4.2 | $18.7 | $41.2M |

| Wind | 8.2 MtCO2e | $1.5 | $18.8 | $12.0M |

| Landfill methane | 4.6 MtCO2e | $2.1 | $17.6 | $9.6M |

| Large hydro | 3.8 MtCO2e | $0.2 | $10.5 | $0.8M |

| Energy efficiency—community-focused | 2.4 MtCO2e | $3.7 | $11.1 | $8.8M |

| Clean cookstove distribution | 2.3 MtCO2e | $5.1 | $23.8 | $11.9M |

| Transportation—private | 1.9 MtCO2e | Not enough price data to report accurate figure | Not enough price data to report accurate figure | Not enough price data to report accurate figure |

| Afforestation/reforestation | 1.3 MtCO2e | $8.1 | $70.5 | $10.6M |

| Biogas | 1.3 MtCO2e | $4.0 | $19.3 | $5.4M |

| Biomass/biochar | 1.1 MtCO2e | $2.0 | $28.5 | $2.3M |

| Improved forest management | 1.1 MtCO2e | $9.5 | $29.1 | $10.1M |

| Water purification device distribution | 1.1 MtCO2e | $5.5 | $13.5 | $5.8M |

| Run-of-river hydro | 956.8 KtCO2e | $1.4 | $8.4 | $1.3M |

| Other | 538.1 KtCO2e | $4.0 | $24.5 | $2.1M |

| Solar | 256.7 KtCO2e | $3.9 | $7.4 | $1.0M |

From the State of Voluntary Carbon Markets report from Forest Trends' Ecosystem Marketplace

Carbon offsets aren’t simple, though. At the outset of the voluntary market’s development, a Financial Times investigation raised concerns about the permanence of the reductions and the additionality of the projects. These concerns still exist. In particular, there’s a continuing problem with low-quality offsets in the voluntary market, which it’s easy to imagine could be problematic: If a purchaser believes their impact is fully offset when it actually isn’t, they may not take further or different actions to mitigate their environmental impact, leaving them likely to be emitting more pollution than intended.

While there’s still work to be done, there are many third-party organizations that have been helpful in producing legitimate projects, enforcing project standards, and providing quality assurance in the offset market. These third-party organizations check several factors, which generally include:

Verification: Did the certifier really visit the project site to make sure it was up and running?

Ongoing verification: Is the certifier routinely checking up on the site to make sure operations are continuing and are accurately measured?

Additionality: Is the site required by law to operate the mitigation technology? Would the project have happened even without the carbon offset revenue?

Leakage: Does preserving a forest, for example, just cause logging to increase somewhere else?

Double counting: Is the offset provider selling the same reductions to multiple buyers?

2) Carbon allowances

Carbon allowances are the permission to emit a given amount of carbon dioxide, generally a ton or metric tonne. (The system of purchasing an allowance is determined by the aforementioned cap-and-trade system).

3) Carbon pricing

In the absence of a strong climate policy framework, many countries and several U.S. states are pursuing carbon pricing policies. This model sets an internal carbon price for emissions, with the goal of incentivizing for “cleaner” company decisions. The price is set by the individual company and then imposed on any of their carbon-emitting operations. By putting a price on pollution, Danny Cullenward, a research associate with Near Zero and the Carnegie Institution for Science, and a lecturer at the Stanford School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences, said he believes this method can be “one of the most effective strategies for addressing the climate problem.”

Some corporations tie the carbon price directly to their procurement processes (e.g., using CO2 calculators when booking air travel), while others implement it during budget calculations (e.g., reporting that division X emitted Y tonnes and “owes” Z dollars this quarter). “The key is to design a strategy that matches (1) your inventory, and (2) your company’s goals,” Cullenward said. BP, the multinational oil and gas company, and Yale University are two examples of how a carbon price can be used effectively, and in different ways, to reduce an organization’s emissions.

From 1998 to 2001, BP—the first-ever company to set a carbon price—reduced its overall emissions by more than 10 percent (1.275 million metric tonnes of C02e). BP used an internal emissions trading system to decentralize the process. Individual business units set their own strategy and could trade emissions credits as long as the overall cap was met.

Yale University, which set its carbon price at $40 per ton, became the first university to approach sustainability in this way in July 2017. They settled on a revenue-neutral scheme, described by the university’s Office of Public Affairs and Communications as follows: “If a building reduces its carbon emissions more than Yale as a whole does, compared to its historical emissions level, then the building receives funds from the carbon charge pool. If the building performs worse than Yale as a whole, then it pays into the carbon charge pool.” Yale aims to be carbon neutral by 2050.

4) Science-based targets

Following the Paris Agreement, 195 government entities committed to keeping global warming below 2 degrees Celsius. A study by McKinsey & Company, a global management consulting firm, noted that while the potential exists to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by just enough to stay on track until 2030, we can miss the target if we don’t take enough action within the next 10 years.

The Science Based Targets initiative, a collaboration between several influential environmental and policy-driven organizations, emerged to help corporations set more globally minded emission reduction targets. It uses various climate-based approaches to determine what portion of the global carbon budget—the remaining amount of carbon that can be emitted into the atmosphere before we hit a temperature level of 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels—an individual organization is allotted. Since the initiative’s inception 337 companies have joined, including Adobe, Nike, Ikea, and VMware.

Although science-based targets are not in themselves a means to carbon neutrality—they’re a target-setting mechanism—they ground reduction goals in the context of the global problem. Organizations can utilize this approach alongside offsetting, allowances, and/or carbon pricing to bring them to net zero emissions, while also being strategic about how to support the global carbon budget. Science-based targets are informed by one of three overarching approaches: The sector-based approach divides the global carbon budget by industry sector; the absolute-based approach assigns the same percentage of absolute emission reductions required globally—49 percent by 2050 from 2010 levels—to each company; and the economic-based approach equates the carbon budget to global GDP and determines a company’s share by its gross profits.

While setting these targets encourages organizations to have a measurable impact, they’re limited in scope. Science-based targets only require including what the Greenhouse Gas Protocol defines as scope 1 (owned emissions, such as natural gas burned to heat your building) and scope 2 (purchased emissions, such as the electricity you buy from utility companies). The majority of an organization’s emissions typically come from scope 3—or indirect—sources, such as travel or server usage.

Here’s how we assessed the four mitigation approaches for Stripe specifically: We felt carbon offsets (when additional) and carbon allowances would allow us to address our emissions at scale, and across all three scopes, while science-based targets and carbon pricing could only be applied to a percentage of our attributable emissions. We wanted net zero, not near zero, emissions.

Through our research, we learned several important things about the industry:

Carbon offsetting is a relatively new phenomenon. This means we have yet to see which approaches will be most effective, or even how significantly they can move the needle on climate change.

There isn’t a “right” way to reduce your impact. Many companies reduce their own emissions, purchase carbon offsets, or do some combination of the two. No solution is perfect, but they are still worthwhile contributions.

There’s no doubt that if more companies were carbon neutral, things would be directionally better. There’s still some disagreement about which methods of reducing greenhouse gas emissions are most effective, but it’s important that we start somewhere—whether by reducing our own emissions, offsetting them elsewhere, or both.

Phase 2: Deciding

We knew we wanted our solution to be quick to implement, high impact, and cost-effective. This meant we could be aspirational in our potential for impact: We were open to all approaches and wanted an above-average impact. But we were also limited by our amount of investment—we had to be realistic with the amount of time we could invest in the program (we had a team of one: me!) and the amount of money we could spend.

Without knowing how large our emissions were, it was also hard to say where our financial limit really was. It was likely somewhere in this range:

This meant carbon offsets or carbon allowances were likely our best bet. To help us decide, we did some Fermi math. Our first iteration of these back-of-the-envelope calculations was based on typical energy usage for an office of our size, the average carbon intensity of electricity on the West Coast, typical server energy usage, and emissions approximations for the amount of travel we engage in. Given that our emissions are unavoidable (we don’t make a physical product), we wanted to include emissions not just from scope 1 and 2, but as much from scope 3 as possible. Many organizations only include direct (heating and cooling) and indirect (electricity) emissions.

With a baseline established, we modeled the costs in more detail by incorporating our own energy data. Using a monthly energy report from our headquarters in San Francisco, we were able to estimate our electricity, heating, and cooling usage for the year. Estimating our server emissions was a bit trickier. We pulled information from our AWS bill and power usage effectiveness numbers from AWS databases, and spoke to our AWS representatives to fill in some gaps. And, finally, for our commute and airline travel, we looked at expense reports and surveyed employees with varying commutes and travel patterns to estimate our annual travel emissions for the year. We then extrapolated these costs across our international office locations and against our five-year headcount projections to get a 2017–2022 model.

Finally, we compared the cost of carbon offsets (using an average voluntary offset price × our 2017 estimated emissions) against the cost of carbon allowances (using the more recent allowance price from the 2017 California cap-and-trade market × our 2017 estimated emissions) to make our decision. Neither amount was trivial, but we determined that carbon offsets would be more attainable for us.

We knew that there were tradeoffs in every approach. Our research led us to four viable options—offsets, allowances, carbon pricing, and science-based targets—which we reduced to one based on the elements we wanted to maximize. If chosen correctly, carbon offsets would allow us to maximize our impact and act quickly, while keeping our costs low: the right solution for us.

Phase 3: Executing

Next it was time to figure out which offset projects we wanted to invest in, focusing on those that were most additional. While many carbon offset projects claim co-benefits to the environment or community, we prioritized being able to reliably measure the amount of greenhouse gas being reduced by the project.

This is a tricky thing to do. Carbon offsets are only effective if the emission reduction truly would not have taken place without your investment (i.e., it’s additional). In order to make a difference for climate change, voluntary carbon offsets should be used to reduce greenhouse gases in places that otherwise would not have an incentive, or their own monetary resources, to do so. But how do you prove that your investment is additional? We studied each individual project in depth to get an answer, primarily focusing on forest and landfill methane projects.

Forest offset projects are effective, but rely heavily on climatic factors. You need to believe that the forest will remain healthy for some significant period of time—what happens if a forest fire or bark beetle kills the forest through no fault of the land’s owner? (In those cases, you may no longer hold an offset.) There is also an inherent time-scale issue. Forest offsets are a promise to prevent greenhouse gas in the future, since the trees need to sequester carbon dioxide over a long period of time without being damaged or burned down.

We felt the additionality argument was clearer with landfill gas collection projects. Firstly, they are more contained: The capturing systems are drilled into the landfill in order to prevent the methane from being released by the decomposing waste. Secondly, federal regulation requires municipal solid waste landfills that hit a certain size/capacity threshold to install a landfill gas capture and destruction system. Many landfills sit below, or may never hit, this threshold, and running the collection system is expensive—it’s rarely economically viable for a business to run one voluntarily.

As with any offset project, there are counterarguments to landfill gas projects. To ensure we were making the best decision, we spent several weeks looking for an offset provider who understood our goals and who worked with a good portfolio of landfill projects in the U.S. We also studied local regulation, community sentiments, and financial history before making our choice.

We partnered closely with that provider to select our offset project, and we just signed on for our second landfill project to cover our 2018 emissions. By purchasing offsets from these projects, the landfills can voluntarily run the collection system—an expensive undertaking they might not have been willing or able to fund alone—preventing thousands of tons of methane from reaching the atmosphere.

In working on this project over the last several months, I’ve become simultaneously frightened about our planet’s future and optimistic about our collective ability to change its trajectory. Carbon offsetting programs like Stripe’s are not an absolute solution to climate change—no single program will be. But by taking action, we can help shape what’s to come. We don’t have to do it—but if we can, we should.

Stripe will be sharing more about the global impact of climate change and our emissions data in the coming months.

Special thanks to Hal Harvey, Emily Grubert, and Tom Stoddard who advised on this piece.

Stripe would like to acknowledge our external partners, NativeEnergy and Ecometrica, and the many experts we consulted for support on this journey.

Considering embarking on your own carbon-neutral journey? Here’s a worksheet to help you along.