Picture around 30 women, between 45 and 60 years old, in an accelerator’s office in Washington, DC. They’re looking at 18 prototypes in simple, static PDF documents—and they’re rejecting them. A crowdfunding platform to help senior women fulfill their bucket lists? The group feels that while crowdfunding is okay, doing so for personal gain is not. An app to spice up the women’s marriages and rebuild their connection to their partners? They initially gravitate toward the idea, but discard it quickly when it seems to imply that there must be something wrong with their marriages.

A group that has historically been underserved by the tech industry, these women are empowered at Hatchery, AARP’s in-house accelerator, where they’re involved from the beginning in the design and development of products that will specifically match their needs.

“There is no substitute for a conversation,” says Alanna Ford, a senior innovation product manager at Hatchery. Based on existing research studies at AARP, Ford and her team conducted several interviews with these women to identify problems that the accelerator could help address: for example, a lack of social connection after their children had left home and a desire to live fully. When Hatchery developed 18 product ideas in response to these needs, it turned them right over to the women.

If the central mission of startups is to make something people want, qualitative research teaches teams what that something is. If a product has already been built, research can uncover whether people want it and how they use it.

For Ford and her team, qualitative techniques such as interviews and usability testing in their labs have helped them assess and quickly discard ideas that didn’t quite click. Five months after commencing research, they were able to build a minimum viable product for the winning prototype: Confetti, a collaboration tool for family and friends to collate pictures of a person’s life.

Quantitative research is considered absolute, though it’s qualitative judgments that determine what data gets measured and how it’s interpreted. Qualitative research can appear vague in comparison, its techniques easily misunderstood and underestimated. But truly understanding users’ experiences with a product requires pulling from many different types of data, from human-centric research as much as code-centric automated tests.

Increment spoke with experts about the role that qualitative research plays in a broad landscape of testing methodologies and data capture: at Google, as it builds an accessible design framework; at Pinterest, as it defined its product strategy in its earliest days; and at AutoCAD, the massive and ubiquitous design and drafting software product, as it decided to go online.

Feeling out Google

Elizabeth Churchill, Google’s UX director and VP of the Association of Computing Machinery, maintains that the distinction between qualitative and quantitative research is not as big as people think. “You can turn anything into numbers,” Churchill says, “and you can interpret anything for meaning.”

Churchill leads research for Google’s Material Design system, which shares components, guidelines, tools, and the open-source code that can help teams build beautiful user interfaces. When it released Material in 2014, Google was not considered an industry leader in design. Now its design system is used as a standard across its own products, and by teams around the world developing for Android, iOS, and the web.

The challenges the project presents are complex: to discover the components that make for usable and beautiful user interfaces, and to release them to a platform where design and development teams from around the globe can access and use them. Components like text fields and buttons are studied and tested down to their individual elements. What is it that makes a button usable for people in diverse contexts? The lines, the movement of shadows, the very atoms of each element need to be tested with real people. In addition, the platform itself must provide all the supportive guidelines, code, and tools that development teams using Material might need.

Churchill has worn many hats: psychologist, social scientist, researcher for safety-critical systems, and, while designing social systems at Yahoo, “Miss Manners of the Web” (as she was titled by the press). She likens Material’s problems to those of Dmitri Mendeleev’s as he tackled the design of the periodic table. In 1869, when Mendeleev first presented his design for the chart, the periodic table was a codification of the known—as well as a provocation to discover the unknown. Today, Material shares and continually updates the best options for user interfaces and enables teams to adapt them for specific use cases, like those unknown to a company of Google’s scale.

The work that Churchill and her team undertake is twofold: They must understand and test for both the developers using Material Design (the makers of an app) and the end users of Material (the users of that app). Central to that work is qualitative research and testing.

Qualitative research can broadly be divided into two forms:

Early-stage qualitative work looks for problems that may not have been adequately solved before. For Churchill’s team, this might mean ethnographic studies of design and development teams in their workplaces.

Late-stage evaluative testing reveals actionable insights into what aspects of an existing product or prototype work—and who cares. For Material, this means testing granular elements and components (such as floating buttons and input fields) in interviews or surveys with end users.

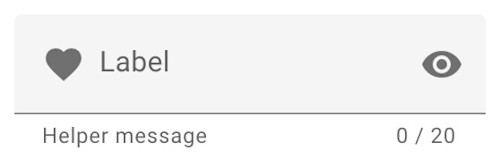

Take this text input field, for example:

Humble as this may seem, it’s a combination of very deliberate choices about label placement, background fill, contrast, and so on, which all come together to determine its usability. To test this usability against specific criteria—Do users know that it’s a text field? Can users fill out a form with these text fields correctly and quickly?—the team performed experimental research.

Churchill and her team built a tool in 2017 that automatically generated text fields of every element permutation (label placement, fill, and so on), and found 144 combinations. These were placed in forms, some the simple kind you regularly find around the web and some the nightmarishly complex and text-heavy kind you hope never to encounter on your screen. Thousands of participants from Amazon’s Mechanical Turk were paid to perform very specific, preset tasks on these forms, with the team tracking their moves and responses.

“Behind every quantitative measure and every metric,” Churchill wrote in a 2012 issue of ACM Interactions, “are a host of qualitative judgments and technological limitations: What should we measure? What can we measure?” Quantitative data is never absolute, she argues.

This project was one of the team’s most comprehensive versions to date of an approach that used experimental condition generators, and the experiment ended in a breathtaking table of data. But participants were also asked to perform qualitative tasks, with the team measuring their emotional responses. That meant people told Churchill’s team that a certain button looked “Google-y” to them, or that it evoked a “warm feeling.”

Churchill says that in such qualitative work—“meaning and feeling work,” as she dubs it—“it’s hard to quantify someone saying, ‘Wow, this feels really good to me.’ You could put it on a scale and say, ‘How good does it make you feel?’ But it’s very different from having a conversation around meaning, from understanding why they feel that way.”

Churchill explains, “The idea of trying to understand people’s feelings, the meaning of something in their lives, how we evoke an emotional response, or how reducing friction might help somebody develop trust in our product—these are very hard concepts to get your head around, if all you’re doing is launching large-scale aggregate surveys.”

The team had never thought to ask respondents, “Does this button look Google-y to you?” This simply emerged naturally during qualitative interviews, as did other questions. “It didn’t occur to us that a warm feeling evoked by a brand could be measured,” Churchill says, “because we hadn’t much experience in that space. But this research project showed us it is possible, and we have since learned about, and have evolved, methods to be able to do so.”

Among the other methods that the team relies on in their evaluative work, Churchill says, are “lab, experiment, interview, observation, reflection, sentiment detection, and so forth. Rather standard kind of evaluation methods, really.” She notes that “the real trick is to triangulate different methods and different data types to generate a deeper understanding of what is going on.”

But the researchers’ data got them questioning the nature of the minuscule yet universally used components that they were designing. Were these components usable to people who weren’t explicitly accounted for in the data that the team had gathered so far? Churchill and her group wanted to reach people with accessibility needs, people with limited access to the internet, people with limited tech literacy, and anyone who’s often left at the margins when developers build for an average user. As the text field study ran, Churchill says, “it became absolutely evident to us that we had not thought through as many of the accessibility issues that were needed, or were being revealed in the study.”

This realization led to the formation of a deep partnership with Google Accessibility. By the end of the evaluative research study, the team had identified one input text field that performed best for most people and over a dozen other options that crossed an acceptable threshold of usability and that they could share with the design and development teams using their platform.

Some people on Churchill’s team like to focus solely on qualitative research and testing, and others solely on quantitative. She says that’s fine: “The job of the team is to make sure these weave together very effectively. The team is very collaborative so this works well for us."

Redrawing Pinterest

“If I was going to advocate for anything, it’d be a bespoke approach,” says Gabriel Trionfi, UX research manager at Lyft and former head of research at Pinterest. Qualitative research is still very nascent in the tech industry, and Trionfi borrows terminology from design and development to describe his process. He believes that the choice of methods should differ based on the situation. This holds true at every step of the process: in the spec, or brief, with its five well-defined points (What is the question? What will we do with the answer? What’s the timeline? Who are the participants and stakeholders? Should I know something that I don’t?); in the research itself; and in its interpretation and presentation. But regardless of the methods used, the research itself should always be well-structured and planned.

“There’s a lot of conversation about evaluative versus formative research,” Trionfi says, and evaluative research is often underappreciated if it doesn’t seem to affect the overall product strategy. Trionfi advocates that evaluative research can also lend impactful and rich insights on users. “If done well, every tactical moment is part of a [product] strategy,” he says.

In his work, Trionfi finds that the richness of a qualitative evaluative study is dependent on the richness of the questions and tasks that comprise it. During his time at Pinterest, Trionfi would sometimes start a study by asking someone to sketch a metaphor or representation of how they saw their relationship with Pinterest.

“People will draw amazing and detailed pictures and they will explain them to you,” he says. The surprise would come when people were asked to redraw the picture at the end of the study. Though sometimes they’d draw the same thing, other times it would be something totally different. Trionfi recalls a case when, using this technique with Facebook’s introduction of a now-deprecated product called Graph Search, a participant’s drawings went from depicting multiple doors that led to people from their past to depicting a focus on the world at large. Trionfi did his PhD in psychology, studying how the inherent structure of play allows people to get into a creative mindset. “When we ask people to engage in intentional creative activities, we see patterns between people and across people and within people,” he says. “It allows us to see something in a different way.”

While most evaluative research and testing leads to smaller changes to the product (e.g., additional features being added or removed), on rare occasions Trionfi has seen it lead to a seismic shift in product strategy. In the early days of Pinterest, the team understood the platform as a social network. Trionfi and the team were studying its follow model—asking who Pinterest users follow and why—and using a typical methodology: a card sort. Trionfi asked people to sort those they followed into groups and explain why these people belonged together. There were piles of friends and family, as expected, but there were also piles for certain types of content. A person interested in a certain type of vintage vehicle was grabbing content on that and following whoever else shared such content too. The piles of people interested in vintage vehicles, cooking, crafting, and so on made it clear that while social connections were important to users, content connections were paramount.

This routine evaluative study—tactical, as Trionfi describes it—delivered far beyond its scope. The company understood that their product was not a typical social network, as they had been thinking about it. Instead, it was a product that people used to catalog their ideas and inspirations.

Late-stage qualitative evaluative work has its own challenges, however. You can’t talk to everyone, so you have to talk to the right people. You also can’t solve everything, so you have to key into what’s relevant—even if it means leaving interesting cases stuck on the corkboard if they are one-offs.

“Your product is a moment in a string of moments which make up a person’s day,” Trionfi explains. Individual experiences are highly diverse, affected by culture, gender, socioeconomics, and a person’s emotional state, among many other factors—all of which influence a person’s behavior and experience using your product. Trionfi says, “The real question is: How relevant is that to a product itself?” And that’s where quantitative data comes in.

Expanding AutoCAD

In the last 20 years, Leanne Waldal has seen companies become more data-driven simply because more data has become available to them. Waldal most recently led research for the enterprise software companies Autodesk and New Relic, but she was also Dropbox’s first head of research and has led her own research agency.

“Companies tend to make a lot of assumptions based on what they see in the data: ‘Oh, there’s a lot of usage of this product—that’s good, people like us,’” Waldal says. “But there’s not necessarily a correlation between a lot of use and likability.”

At Autodesk, Waldal oversaw research to bring AutoCAD—the industry-standard design and drafting software application used in architecture, engineering, construction, and manufacturing—online as a fully functional web app. People don’t shy away from qualitative research due to “fear of what they’ll learn,” Waldal says. “It’s more that they think they already know.” AutoCAD had many stories about how people used its software, but these accounts were outdated.

The team opted not to interview and remotely observe a large number of companies across geographies and industries in a broad qualitative study. Instead, they visited only North American companies across two industries for an in-depth investigation.

When possible, Waldal prefers to embed researchers in small multidisciplinary teams consisting of a product manager, engineer, and designer. The overall research is then dual-tracked: some will be fast, guiding the team’s decisions from sprint to sprint; some will be more intentional and slow, feeding the company strategy for years. A large part of any research project or test is about navigating access to end users, so in enterprise software in particular, where the buyer of the company’s product isn’t necessarily the end user, Waldal uses something called a RACI model to ensure that all stakeholders are kept in the loop. This model is used to assign roles and responsibilities for a project by helping the researcher identify those who are Responsible or Accountable for the project, who needs to be Consulted, and who has to be kept Informed. Starting a project with thoughtfulness, Waldal believes, is critical to ensuring that the research has an impact.

A similarly small multidisciplinary team spearheaded the on-site visits for the AutoCAD study, and members jointly interpreted their findings on their return: an unusual level of collaboration in the field of qualitative research.

To their surprise, they found that several companies using AutoCAD in different industries used a similar hack—often copied onto a Post-it and stuck on employees’ monitors—that allowed the companies to use the software in a way that the research team might not have discovered otherwise, and which could potentially be addressed via a redesign.

“How do we know that people at, say, 10 companies represent our, say, 50,000 customers?” Waldal asks. One method is to use analytics as well as surveys to investigate interesting leads that the research may have observed only once. Sometimes those results show that single instance affecting 50 percent of the people surveyed. “We wouldn’t have known that unless we specifically asked them about that in a survey,” she points out.

A different kind of test

If quantitative data can bolster qualitative insight by declaring it statistically significant, qualitative insight can bring meaning and significance to a mere blip in the quantitative data. In trying to understand the usability of a product, testing methodologies that may seem distinct actually work in concert. And, ultimately, it’s all about the user.

Waldal likes to think of qualitative and quantitative data in addition to analytics as three different levels: “Qualitative is very enclosed and deep: You get a lot of information from a [small] number of people. Quantitative research, when you move into a survey, is not as deep: You get a medium amount of information from a lot of people. In analytics”—that is, big-picture views of user activity—“you get a smaller, more controlled amount of information from a massive number of people.”

When you can tell a story across data types, you can holistically capture a human experience. And when Google, Pinterest, AutoCAD, and AARP combined insights from these varied and powerful testing methodologies, they could begin to solve the riddle of usability.